POOR, PITIFUL ME

How Poverty Shaped Me Into the Woman, Artist, and Activist I am Today and Why it’s Important

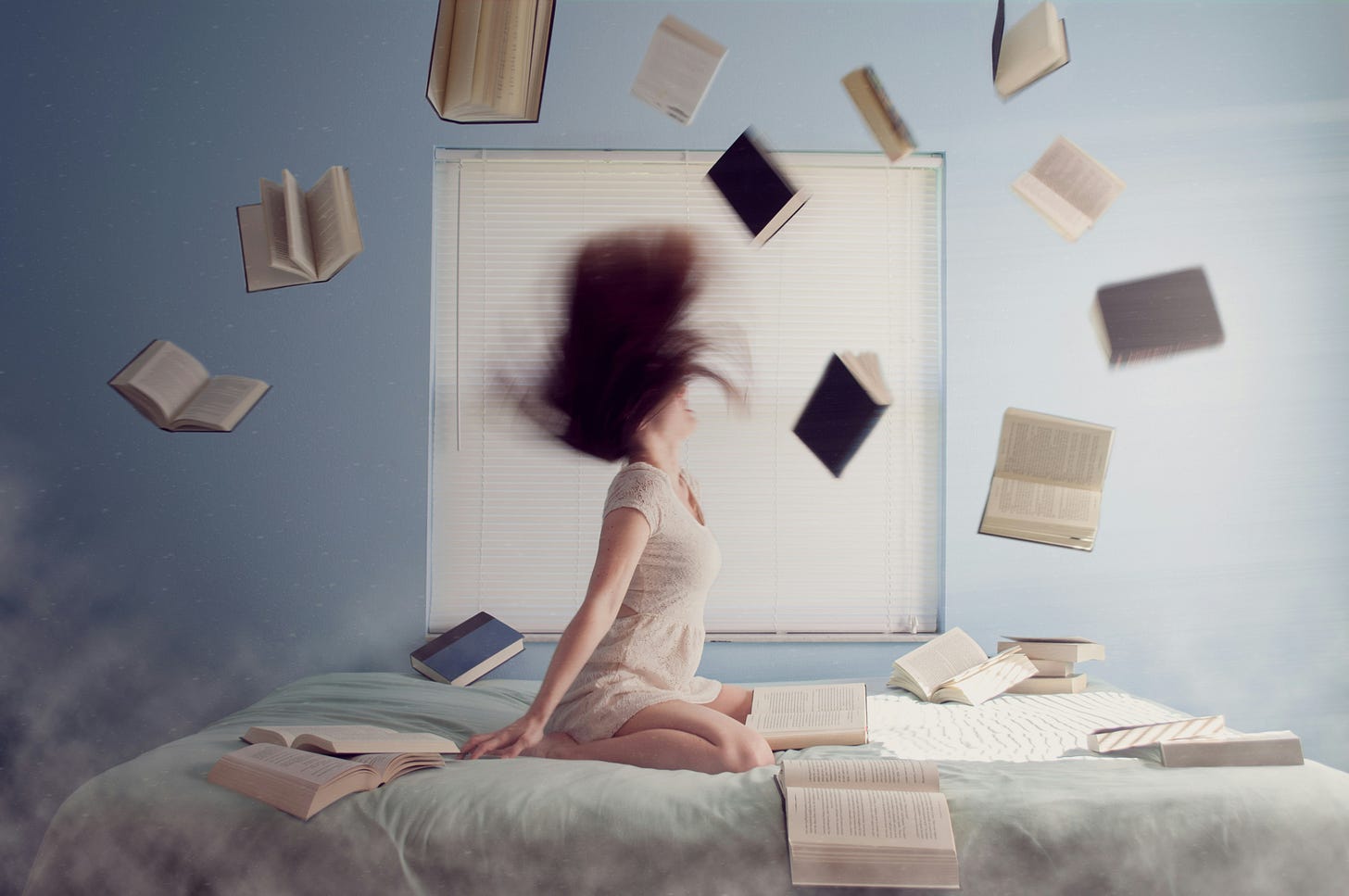

Ignoring dire circumstances as much as humanly possible is how I sometimes managed to hover above the daily horrors of my childhood and young womanhood. The magic trick of being fully immersed in terror and then temporarily rising out of the mire was not the result of smoke and mirrors. Rather, these sparse triumphs tumbled skyward on the papered wings of reading and writing.

The fact that art saved—saves—me is true to this day. If I didn’t snap shut my doom scrolling with a deep dive into literary and other artful pursuits, I’d become caged in grief, anger, despair.

Despite my magical abilities born of books, poverty is a fog that seeps into all of my literary spaces. I might be, for instance, the workshop leader, but usually I’m the only one who grew up on welfare, with one parent, in conditions so squalid and violent that if it were happening today, my sister and I would be yanked from the home. Indeed, I sit around our digital Zoom table and listen to the poor being referred to as “those people” and “those people” get blamed for all manner of things they aren’t exclusively responsible for—Trumpism, domestic violence, Christian nationalism to name a few—and though, with varying degrees of success, I attempt to keep my voice steady, in my heart and brain, sinew and synapse, I’m screaming.

Inevitably, I out myself—I grew up desperately poor or We lived in a tiny, vermin-infested, wheel-less pull behind with no heat or ac and often no electricity that I called The Blister or Our house was so overridden with roaches, they fed on my skin as I slept and my mother always brightly said, “Don’t worry; they’re just nibbling a little.”

Yes, I say these things, but I’ve come to recognize that for some folks poverty is a distant shore, yet one more Other, and to imagine what it’s like to watch your mother attempt to stretch that watery broth for one more night or watch her shape paraffin wax into a tooth under scalding water because her dead husband knocked out her incisor when he was alive and dentists are far beyond our reach, or going with her to the pawn shop to pawn my sister’s wedding gifts so our electricity can be turned back on, is incredibly difficult, nigh to impossible if you haven’t walked in shoes with more holes than soles.

I’ve come to understand that plenty of privileged people hate poor people and not out of malice but because they’re scared they might become one of us. I have compassion for that. I’m scared that one day I’ll wake up and look like a heroin-ized, American South version of Zsa Zsa Gabor. But I refuse to hate Zsa Zsa even if I can’t fully decode what life is like for a ridiculously rich, diamond-draped, Hungarian socialite.

Here me roar: Literary spaces should never be devoid of empathy and compassion. But this absence is real. The virtue deficit arises whenever a story surfaces about domestic violence—Why doesn’t she just leave?—and I have to put on my activist cap and explain to the person who, again, asked the question out of naivety, not malice. When race is discussed, often the opposite happens; a well-meaning white person will white-splain to the person of color what the person of color’s experience is. Again, not malice, but definitely wrong-headed.

When class and poverty are the topics, I hear a lot of blame, the undercurrent being people are poor because they’re lazy, and our country is in the shape it’s in because poor people vote against their own interests (the wealthy carried Trump into the White House in 2016 and those numbers only marginally ticked down in 2024). I avoid offering long explanations about how difficult it is to find affordable housing, especially since first, last, and damage deposits can snowball into a down payment equal to purchasing a house. Or how landlords require renters to meet impossible thresholds, including impeccable credit, something that is becoming an unreachable goal for increasing numbers of Americans. I don’t explain that if you’re poor, proper nutrition is an issue, medical care is an issue, transportation is an issue, education is an issue, environmental safety is an issue, housing is an issue. I don’t explain that these insurmountable hurdles keep people trapped in poverty.

I don’t blather on because these truths, at least to me, are self-evident. That, and I don’t relish the role of Poverty Tour Guide. So I say less and fume more.

And that has to stop.

The writer Lee Cole has an article on Lit Hub titled, “What Does it Mean to be a Working Class Writer at Iowa Writers’ Workshop: Lee Cole on the Absence of Working Class Perspectives in Our Literary Institutions.” Cole writes, “While institutions—MFA programs, lit mags, publishing houses—have done much to include and elevate underrepresented groups on the basis of race, gender, or sexual orientation, they’ve done far less to include and elevate those from underrepresented class backgrounds.”

This is certainly true at the MFA program I taught at for fifteen years. As we rolled out long-overdue DEI programs and policies, I, along with students from working class and poor backgrounds, brought up the issue of class, asking that we do exactly what Cole calls for—“. . . include and elevate those from underrepresented class backgrounds.” To say that these suggestions were scoffed at is an understatement. An administrator actually rolled her eyes at me when I made the case for said elevation.

When I enter a room full of, for instance, wealthy library patrons (God bless them; we need people who support the arts now more than ever), I feel like an imposter, as though the stench of poverty clings to me. And maybe it does. Because I can’t tell you how many times 24 karat gold-plated ladies at literary events corner me and say, pretty much verbatim, “You made it out. What can’t they? What’s wrong with them?”

I hide my hurt and anger behind my magnolia smile and attempt to explain, but I never get very far because their eyes glaze over and they wander off while I’m in mid-sentence.

We do a lot of blaming in this country. But we’re terrible at elevating. In fact, I might sound like I’m blaming rich people for their often terrible attitudes about the poor (let’s be honest; there is no way Elon Musk could enter my childhood and survive). But I’m not blaming, not really. I’m pushing open a window, asking for a conversation, hoping that our literary institutions will lead the way, because if the voices of the poor and formerly poor are not heard, we as a nation are truly impoverished, our moral center shattered amid the gold toilets of the few.

ON THE ROAD!

This Friday InkBlossom’s Vermont Novel Retreat kicks off in Stowe, a ski village that’s awfully nice in the summer, too. I can’t wait for my extended family of writers to join together for a week spent immersed in their writing and community.

At these retreats, I offer micro-lectures on books I love. Here’s my list for this year’s retreat. It’s a sweet combo of old and new, featuring novels, short story collections, and an enduring climate memoir:

· Richard Bausch’s The Fate of Others

· Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

· Samuel Kolawole’s The Road to Salt Sea

· Amity Gaige’s Heartwood

· Jill McCorkle’s Old Crimes and Other Stories

· Ocean Vuong’s The Emperor of Gladness

PS: InkBlossom offers scholarships for all of our offerings, making events accessible for rich, middle class, working class, and poor alike.

COMING UP!

InkBlossom’s Santa Fe Writers’ Retreat and Conference and our virtual Fall Retreat.

Also, in July, get ready because I’m launching my love project: Coco May Studios.

HARD WON ADVICE!

Don’t doom scroll. Write!

Thank you for writing this, Connie. It's incredible. I know people could look at me now and think i'm privileged, which i guess i am, but to me i'm always that girl that grew up getting the electricity and phone cut off because we couldn't pay the bills, getting evicted because we couldn't pay the rent, no washer or dryer, people screaming and fighting and scrabbling to survive, and working at 14 because i had to, feeling so much shame. I think that's why I understood China so well and my friends when i lived there. They were scrabbling, scrabbling to survive in a way i completely understood. We got each other. Thanks again, xo

You never stop being that poor girl no matter how the rest of your life unfolds. You never stop feeling like an outsider, even in supposedly inclusive spaces.

You're reminded every time someone tells you it's unrealistic for your character to not know what size a grapefruit is because they couldn't afford to buy produce or how it's melodramatic for a character to fill an empty soap bottle with water to get the last bubbles out because they know their parents can't afford more. And their shock and discomfort when you tell them those are your own experiences or their insistence that "people who read" won't relate or understand (translation: "Only people with money read") makes you feel even more like an alien. It makes me want to scream about how I was homeless as a child and teenager, and during those times, books were the only things that kept me sane.

We, the literary community, need to do better. Thank you for writing this. Sharing, even when it's extremely uncomfortable, is the only way we make people listen, and it's the only way we fix the problem.